The DAD Framework: Building Developmentally Aligned Design for All Ages

- David Ruttenberg

- 1 hour ago

- 7 min read

Most AI systems are designed for a phantom user: neurotypical, non-disabled, and resilient to cognitive overload. The rest of us? We’re expected to adapt, or drop out.

Here’s the problem: this is the Missing Level of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs—what it takes to thrive in a sensory-laden, distracting, anxiety and fatigue-producing world. Not just survive. Not just comply. Thrive.

Most AI systems--including yours--are using the wrong model. It’s not just inefficient; it’s unethical. And it’s costing organizations billions in lost productivity, turnover, and litigation risk (Kurian, 2025).

Developmentally Aligned Design (DAD) flips the script. Instead of building systems that demand human accommodation, I help build systems that accommodate human variability, especially for neurodivergent employees, students, patients, and citizens who've been systematically shut out by "one-size-fits-all" interfaces.

We don’t ask people to “build resilience” to toxic air—so why do we ask people to “build resilience” to toxic computer interfaces?

This isn't theory. It's a three-layer audit and design framework I use with government agencies, Fortune 500s, and higher education institutions to rebuild AI systems from the ground up.

Because dignity isn't a feature request. It's the foundation.

Layer One: Human Factors Safety (Bio-Cognitive Response)

The base of the DAD pyramid is Human Factors Safety—the biological and cognitive conditions that determine whether a person can safely engage with a system without harm. When I say “Human Factors Safety,” I explicitly mean the Bio-Cognitive Response dimension: what the interface does to your body, brain, and stress physiology in real time (Ruttenberg, 2025; Van der Kolk, 2014).

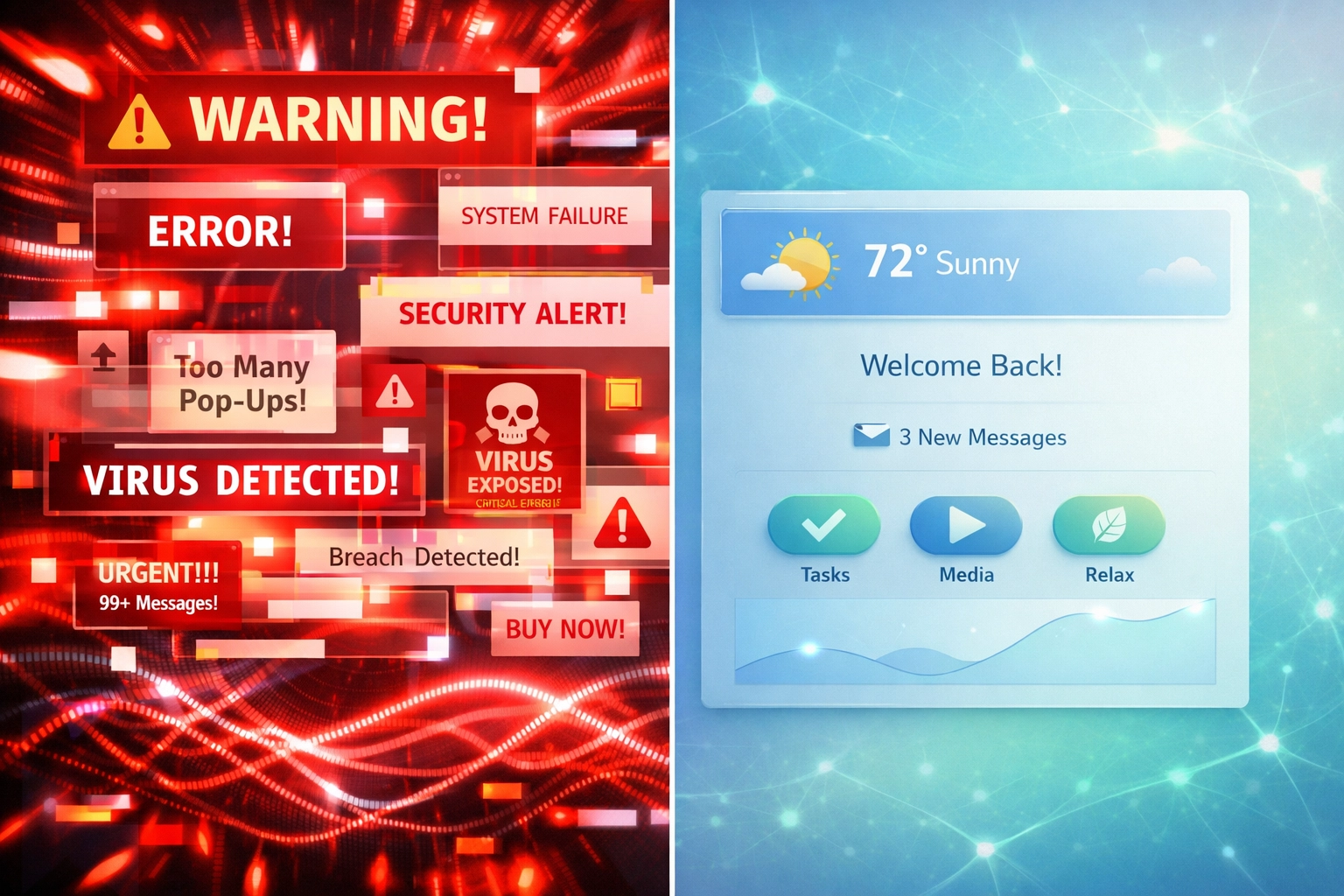

This layer asks one question: Does this system respect the user’s nervous system—or does it override it?

And here’s the human part we too often bury under “UX requirements”: mental health is a safety metric. Not a “wellbeing add-on.” If your system reliably drives anxiety, fatigue, panic, shutdown, or post-use crash, that’s not “engagement.” That’s harm (Van der Kolk, 2014). In Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) especially, where one burned-out person can take a whole workflow down, these impacts show up fast: sick days, errors, churn, silence.

For neurodivergent users, autistic adults, ADHD employees, trauma survivors, the answer is often no. Flickering animations trigger migraines. Autoplay video floods sensory channels. Notification cascades spike cortisol.

These aren’t minor annoyances; they’re bio-cognitive violations that can destabilize users for hours or days (Bogdashina, 2016).

Think: Sensory Sensitivity➔Distractibility➔Anxiety, Fatigue, Poor Performance.

In my consulting practice (davidruttenberg.com), I audit for core safety metrics like:

Sensory load: Are there strobing elements, sudden audio cues, or high-contrast flashes that trigger sensory overload or seizures?

Cognitive demand: Does the interface require simultaneous processing of multiple streams (e.g., chat + video + shared screen) without pause controls?

Mental health impact (anxiety, fatigue, shutdown): Does the system create panic via time pressure, induce chronic tension through constant alerting, or leave users depleted after use?

Stress response: Are error messages punitive or shaming? Do time limits, “nags,” and surprise popups induce panic?

We don’t ask people to “build resilience” to toxic air—so why do we ask people to “build resilience” to toxic interfaces?

My work with Phoeb-X, informed by my thesis research on the Sensory-to-Mental Health Digital (S²MHD) model (Ruttenberg, 2024), demonstrated how aligning sensory input with cognitive load reduces performance anxiety and fatigue.

Human Factors Safety isn’t about making systems “easier.” It’s about making them survivable—calm, predictable, humane...and helping people thrive.

Layer Two: Developmental Fit (Sensory Architecture + Lived Experience)

The middle layer is Developmental Fit: how well the information environment matches real human development, real human context, and real human limits. Yes, this includes Sensory Architecture—the ergonomics of the environment—but it also includes something engineering teams routinely miss: lived experience (Van der Kolk, 2014; Local Government Association, 2023).

This is where we move from “does this hurt?” to “does this help?”—and from “we built it” to “we built it with you.” Because “good design” isn’t what passes a spec review. “Good design” is what a tired parent can use at 11:47pm, what an overwhelmed student can navigate mid-shutdown, what an exhausted employee can handle on their third meeting-heavy day in a row.

For SMEs, this is a superpower. You don’t need a moonshot lab. You need short feedback loops, community participation, and the humility to treat users as co-designers: designed by the community, for the community.

Key audit dimensions:

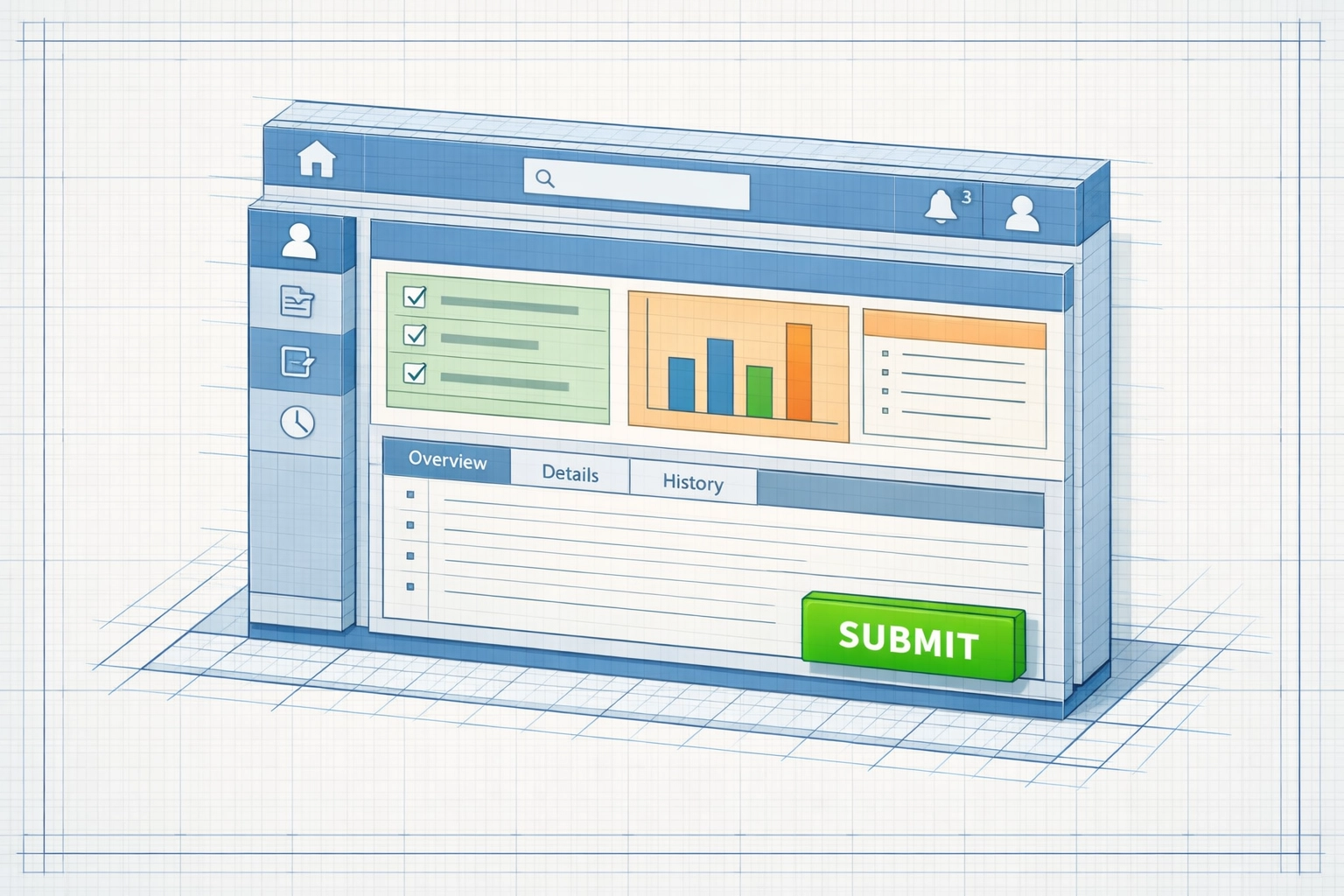

Visual hierarchy: Is the most important action obvious within 2 seconds, or is the user scanning a cluttered dashboard?

Navigation persistence: Can users return to a known anchor point (e.g., home, dashboard) from anywhere in the system?

Sensory consistency: Do button shapes, colors, and placements remain stable across workflows, or does each screen require re-learning?

Lived experience coverage: Were autistic, ADHD, disabled, and caregiver voices in the room early—paid, credited, and listened to—or consulted at the end as “validation”?

Community co-ownership: Are there ongoing channels (advisory groups, office hours, co-design sprints) where the community can steer priorities, not just file bugs?

I worked with a university learning management system (LMS) that had 17 different icons for “submit assignment”: some green, some blue, some at the top of the page, some at the bottom. Autistic students were spending 10+ minutes per assignment hunting trying to find the right button. We standardized the submit action: same icon, same color (green), same position (bottom-right). Submission errors dropped 68% in the first semester (Ruttenberg, 2023).

Developmental Fit is environmental ergonomics plus community truth: we design the accommodation, the room, the technology—not the occupant... and we design it to meet the occupant’s personalized needs. Again...we don’t expect them to be resilient to toxic air.

Layer Three: Cognitive Advocacy (Executive Function and Dignity)

The peak of the pyramid is Cognitive Advocacy: systems that actively support executive function and protect user dignity (Kurian, 2025).

This layer is where most AI fails neurodivergent users. Instead of scaffolding decision-making, systems demand it. Instead of building confidence, they punish errors. Instead of respecting autonomy, they surveil and nudge.

Cognitive Advocacy asks: Does this system treat the user as a problem to be managed, or a person to be supported?

In practice, this means:

Error tolerance: Undo/redo functions, autosave, and non-punitive error messaging

Transparency: Explaining why the system is making a recommendation, not just what it recommends

Agency: Allowing users to disable adaptive features, reject suggestions, and opt out of data collection without penalty

One federal agency I consulted for had built an "adaptive learning" onboarding AI that tracked employee hesitation (mouse hover time) and flagged users who took "too long" on training modules. Managers received automated reports labeling employees as "at-risk learners." Neurodivergent employees: who often take longer to process information but achieve identical or superior outcomes: were being systematically flagged as under-performers (Local Government Association, 2023).

We rebuilt the system to remove behavioral surveillance and replace it with opt-in scaffolding: users could request hints, extended time, or simplified instructions without triggering a flag. Completion rates increased. Stress complaints disappeared. And the agency avoided a discrimination lawsuit.

Cognitive Advocacy is about dignity by design: systems that assume competence, not deficiency.

Why This Matters Now

AI is being deployed faster than we can audit it. Mental health chatbots, classroom engagement trackers, workplace productivity monitors: they’re all designed for the “average” user, a statistical fiction that excludes a lot of real humans (Ruttenberg, 2023).

The cost of exclusion is staggering: turnover, litigation, lost innovation, and: most importantly: human harm. Neurodivergent employees and students are canaries in the coal mine. When systems fail them, they're failing everyone; the rest of us just don't notice yet.

The DAD Framework offers a roadmap: start with biology, build the environment, protect dignity. It's not about making AI "nice." It's about making AI ethical: systems that respect the users they claim to serve.

As our daughter Phoebe (now 23, autistic, ADHD, and epileptic) navigates a world increasingly mediated by algorithms, I'm reminded daily that the stakes are existential. She deserves systems designed with her neurology in mind, not despite it. So does every other neurodivergent person trying to work, learn, and live in a world that too often mistakes difference for deficiency.

Where to Start

If you're a CXO, agency lead, or higher ed administrator wondering whether your AI systems meet DAD standards, here are three questions to ask your team tomorrow:

Have we audited for sensory harm? (seizure risk, overload triggers, stress responses)

Can neurodivergent users navigate our system without cognitive penalty? (time limits, error shaming, cluttered interfaces)

Does our AI assume competence, or does it surveil and flag "atypical" behavior?

If you can’t answer yes to all three, let’s talk. I audit, redesign, and train teams to build systems that work for all nervous systems: not just the mythical average one.

Email me at davidruttenberg@gmail.com.

Because the future of ethical AI isn't about building smarter machines. It's about building kinder ones.

About the Author

Dr David Ruttenberg PhD, FRSA, FIoHE, AFHEA, HSRF is a neuroscientist, autism advocate, Fulbright Specialist Awardee, and Senior Research Fellow dedicated to advancing ethical artificial intelligence, neurodiversity accommodation, and transparent science communication. With a background spanning music production to cutting-edge wearable technology, Dr Ruttenberg combines science and compassion to empower individuals and communities to thrive. Inspired daily by their brilliant autistic daughter and family, Dr Ruttenberg strives to break barriers and foster a more inclusive, understanding world.

References

Bogdashina, O. (2016). Sensory perceptual issues in autism and Asperger syndrome: Different sensory experiences, different perceptual worlds (2nd ed.). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Kurian, P. (2025). Developmentally aligned design: A framework for ethical AI in child-facing systems. Journal of Digital Ethics, 4(1), 22–41.

Local Government Association. (2023). Safeguarding autistic adults: A framework for local authorities. https://www.local.gov.uk/publications/safeguarding-autistic-adults

Ruttenberg, D. (2023). Invisible disabilities and workplace accommodation. POSTnote 689, UK Parliament POST. https://post.parliament.uk/research-briefings/post-pn-0689/

Ruttenberg, D. (2025). Mitigating sensory sensitivity in autistic adults through multi-sensory assistive wearable technology [Doctoral dissertation, University College London]. UCL Discovery. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10210135/

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Comments