The Realism Era: What AI Is Actually Doing to Our Brains

- David Ruttenberg

- 1 hour ago

- 5 min read

I think we're entering a new era of AI.

Not a new model. Not a new headline. A new mood.

For the last few years, we've been stuck in what I'd call the promise economy: AI is going to change everything, fix everything, scale everything. But there's a shift happening now: what some folks are calling the "Realism" era. According to the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI, we're moving from "Look what AI could do" to "Show me what AI actually does in real life" (Stanford University, 2024). That's a healthy shift. And it couldn't come at a better time.

Because if we're going to talk about "real-world utility," we also have to talk about real-world biology.

Real Impact Looks Like: Attention, Sleep, Stress, and Self-Trust

When AI enters daily life, it doesn't enter as an abstract tool. It enters the nervous system.

It touches attention (what gets pulled, what gets fragmented). It touches sleep (what gets delayed, what gets stimulated). It touches stress physiology (what keeps the threat system online). And it touches self-trust (what makes us outsource decisions we used to make internally).

Recent research from MIT reveals something striking: ChatGPT users showed the lowest brain engagement compared to those using search engines or writing independently (Eaton, 2025). Here's the kicker: 83% of ChatGPT users couldn't remember passages they had just written. They bypassed deep memory processes entirely. Meanwhile, the brain-only group demonstrated the highest neural connectivity, particularly in alpha, theta, and delta brain waves associated with creativity, memory, and semantic processing (Eaton, 2025).

The efficiency trade-off is significant. ChatGPT users wrote 60% faster, but their "relevant cognitive load": the intellectual effort needed to transform information into knowledge: fell by 32% (Eaton, 2025). Convenient? Yes. Good for your brain? That's the question we're not asking enough.

So in the Realism era, the right question isn't just "Is it accurate?" It's: What does it do to the person using it?

AI + Neuroscience Is Colliding in "Personalized Mental Health"

One of the biggest places we'll see this realism test is mental health.

There's a growing push toward what gets called personalized mental health: using wearables and behavioral data to reduce the guesswork in treatment. Recent work on digital phenotyping from wearables shows AI can characterize psychiatric disorders and even identify genetic associations (Liu et al., 2024). In theory, this can help people skip the exhausting trial-and-error loop: try a technique, wait weeks, see side effects, switch, repeat.

Instead, the promise is: we can detect patterns sooner: sleep disruption, stress spikes, attention collapse, early relapse signals: and adjust faster.

I'm not dismissing this. For some people, it could be life-changing.

But here's the part I need us to say out loud: The more personalized it gets, the more it needs to be humane.

Because it's one thing to "optimize outcomes." It's another thing to live inside an always-measuring system that quietly trains you to feel monitored.

The Problem Isn't Data. It's Sensory Load.

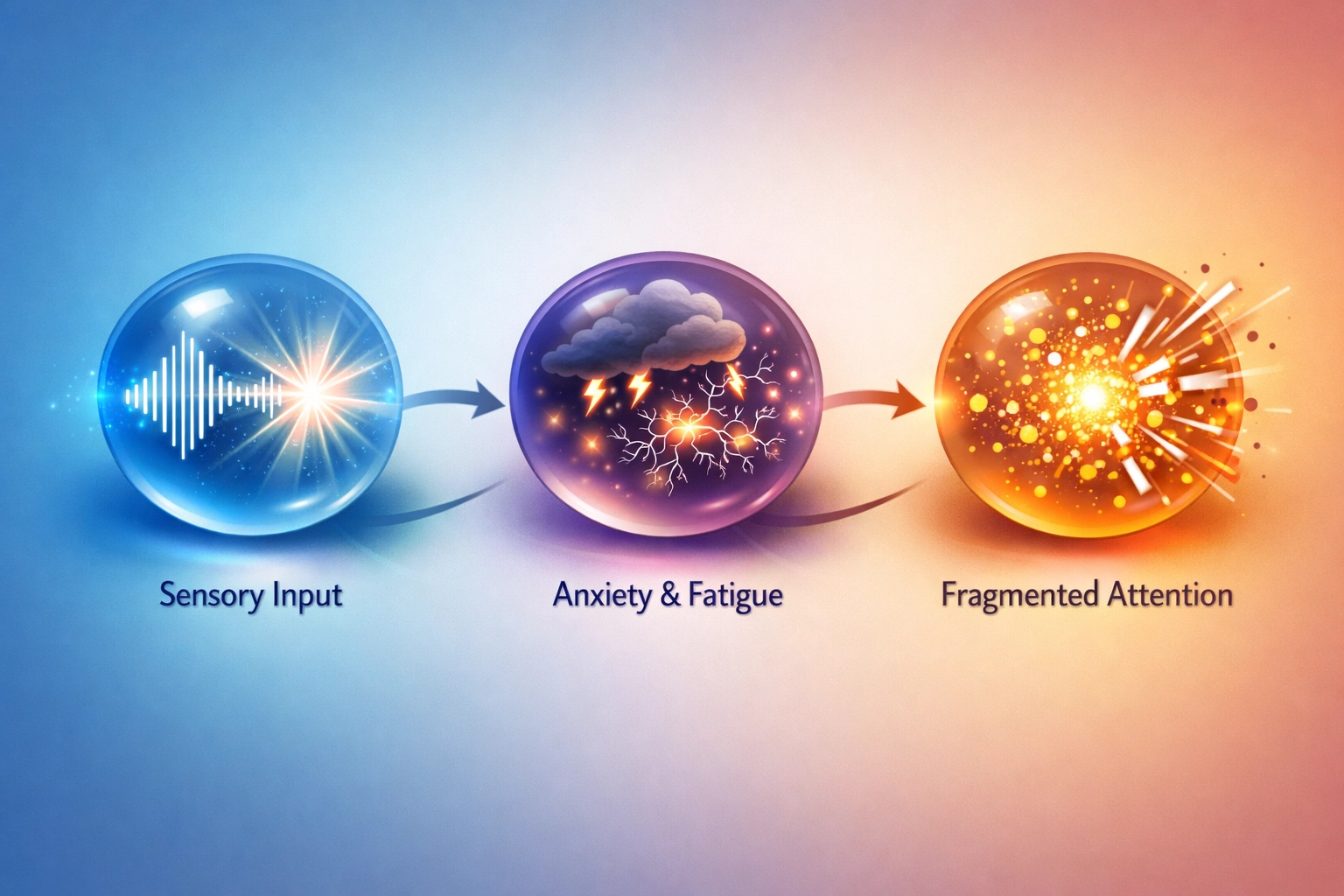

This is where my own framework keeps coming back: sensory sensitivity and neurodivergent accommodation. In my doctoral research, I developed the Sensory Sensitivity Mental Health Distractibility model (S2MHD), which illustrates a new autistic pathway from sensory cues (sensitivity) through mental health (anxiety and fatigue) to distractibility (attention): a relationship only previously suggested for non-autistic individuals (Ruttenberg, 2023).

A lot of AI design assumes a "default" brain: stable attention, low sensory sensitivity, predictable motivation, high tolerance for interruptions, easy emotional recovery.

That's not reality for many people. Especially neurodivergent people. Especially people under chronic stress. Especially teenagers (more on that in another post).

If we build "personalized mental health" tools without accommodating sensory load, we risk creating something that looks supportive but feels like pressure. And pressure doesn't heal nervous systems. It tightens them.

Neuroscientists are already expressing concern about cumulative "cognitive debt": as automation increases, the prefrontal cortex (critical for reasoning and problem-solving) is used less frequently, potentially causing lasting effects beyond individual tasks (Eaton, 2025). In developing brains especially, the neural connections that help you access information, form memories, and build resilience can weaken with overreliance (Eaton, 2025).

What I Want the Realism Era to Measure

If we're finally measuring real impact, here's what I hope we measure: not just engagement, not just "symptom check-ins," but deeper questions:

Does this tool reduce cognitive burden or add to it?

Does it improve self-understanding or replace it?

Does it support agency or subtly erode it?

Does it calm the nervous system over time?

Does it work for the people who don't fit the default user?

That's the realism test I care about.

Research already shows that how we use AI fundamentally determines whether it enhances or diminishes our cognitive abilities. When students were trained to write first and then given AI tools, they showed significant increases in brain connectivity. But those who relied on ChatGPT from the start performed poorly when later asked to write without it (Eaton, 2025).

The critical distinction is between passive offloading versus active engagement. Generative AI boosted learning for users who engaged in deep conversations and explanations with it, but hampered learning for those who simply sought direct answers (Eaton, 2025).

The Book Thread I'm Building

The book I'm working toward is essentially about this: how we design environments: digital and physical: that don't punish sensitive nervous systems.

AI can be a supportive layer. Or it can be the latest layer of overload.

The Realism era gives us permission to stop guessing and start being honest. And honesty is where good design begins.

So here's my call to action: Before you implement the next AI tool in your organization, your school, or your home: ask not just "Will this save time?" but "Will this support the nervous systems of the people using it?"

That's the question that separates promise from reality.

About the Author

Dr David Ruttenberg PhD, FRSA, FIoHE, AFHEA, HSRF is a neuroscientist, autism advocate, Fulbright Specialist Awardee, and Senior Research Fellow dedicated to advancing ethical artificial intelligence, neurodiversity accommodation, and transparent science communication. With a background spanning music production to cutting-edge wearable technology, Dr Ruttenberg combines science and compassion to empower individuals and communities to thrive. Inspired daily by their brilliant autistic daughter and family, Dr Ruttenberg strives to break barriers and foster a more inclusive, understanding world.

References

Eaton, K. (2025, January 28). Does AI make you dumber? New brain study reveals shocking truth. Neuroscience News. https://neurosciencenews.com/ai-cognition-memory-28641/

Liu, J. J., Kumar, P., Raj, P., Faraone, S. V., & Smoller, J. W. (2024). Digital phenotyping from wearables using AI characterizes psychiatric disorders and identifies genetic associations. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.23.24314219v1

Ruttenberg, D. (2023). Multimodality and future landscapes: Meaning making, AI, education, assessment, and ethics [Doctoral dissertation, UCL Institute of Education]. UCL Discovery. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10210135/

Stanford University. (2024). AI Index Report 2024. Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI).

Comments