The Ethics of Mental Health Wearables: Monitoring Anxiety Without Crossing the Line

- David Ruttenberg

- 4 days ago

- 5 min read

Wearables that track your heart rate, sleep, and stress levels are everywhere now. Your smartwatch probably already knows when you are anxious before you do. But here is the uncomfortable question nobody wants to ask: just because we can monitor mental health through technology, does that mean we should?

The answer is not a simple yes or no. It depends entirely on how we build these tools, who controls the data, and whether users actually understand what they are signing up for.

The Promise and the Problem

Mental health wearables have genuine potential. For people living with anxiety, autism, or other conditions that affect daily functioning, real-time biometric feedback could be transformative. Imagine a device that notices your stress levels rising and gently prompts you to take a break before you hit a meltdown. That is not science fiction. That is the direction we are heading.

My own research on multi-sensory assistive wearable technology focuses on exactly this kind of support, particularly for autistic adults experiencing sensory overload (Ruttenberg, 2025a). The goal is not surveillance. The goal is empowerment.

But here is where it gets tricky. The same technology that could help someone manage anxiety could also be used to monitor employees, screen job applicants, or sell your emotional data to advertisers. Research has found that 29 of 36 top-ranked mental health apps shared user data with Google and Facebook in ways that user agreements did not clearly disclose (Huckvale et al., 2019).

Mental Privacy: A New Frontier

We talk a lot about data privacy. But mental health wearables raise a different kind of concern that researchers are starting to call "mental privacy," which is the right to keep your inner mental states to yourself (Burr & Cristianini, 2019).

Think about it. Your heart rate data is one thing. But a device that infers your mood, your anxiety levels, or your emotional state? That is getting into territory that feels fundamentally different. It is not just about what you do. It is about what you feel.

In my PhD research, I explored how technology could support autistic adults without crossing into invasive territory (Ruttenberg, 2025b). One of the key findings was that ethical wearable design must prioritize user control. People need to decide when, how, and with whom their data gets shared. Full stop.

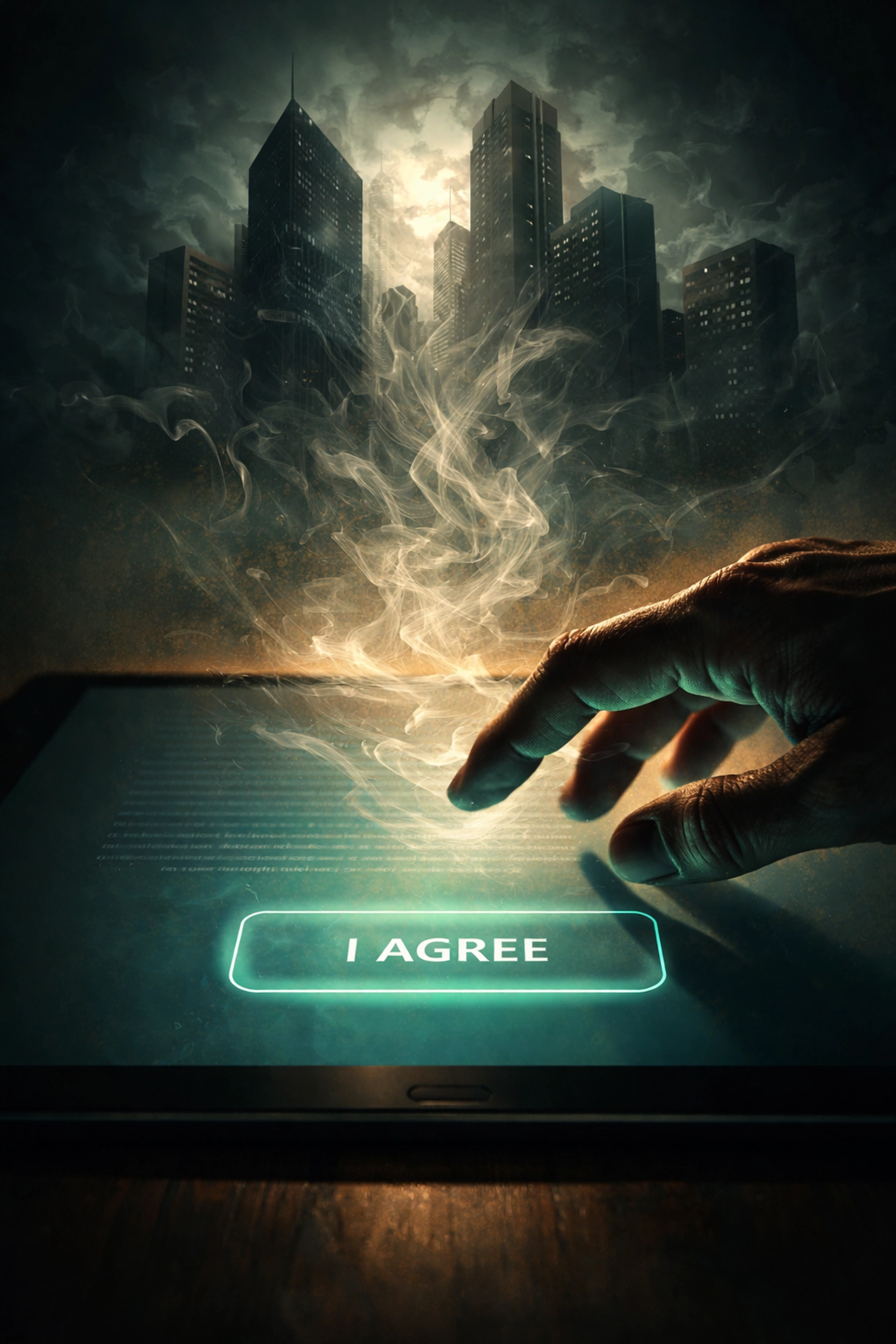

The Consent Problem

Here is a scenario that happens all the time. You buy a smartwatch. You click "I agree" on the terms and conditions without reading them because who actually reads those things? Congratulations, you have just given implied consent to data practices you do not fully understand.

This is a fundamental autonomy problem. Users often consent to things they would never explicitly approve if they understood the full picture (Burr & Cristianini, 2019). And this gets even more complicated for vulnerable populations.

My work on safeguarding autistic adults who use technology highlighted how individuals with intellectual disabilities, students, and other groups may have diminished capacity to make fully informed choices about digital tools (Ruttenberg, 2023). We cannot assume that clicking "agree" equals genuine informed consent.

Transparency and the Black Box Problem

Another ethical landmine is transparency. Commercial wearables frequently oversell what they can do. Sometimes they measure less than promised. Sometimes they measure more than users consented to (Burr & Cristianini, 2019).

Either way, users are left in the dark. How does your device decide you are "stressed"? What algorithm is making that call? Can you question it? Usually, the answer is no. The device is a black box, and you just have to trust it.

This undermines user agency in a fundamental way. If you cannot understand, negotiate with, or question how a device reaches conclusions about your mental state, are you really in control?

In the PPI questionnaire I developed for the SensorAble research project, one of the core priorities was ensuring that any adaptive wearable intervention remained transparent and user-directed (Ruttenberg, 2020). People should not be passive recipients of algorithmic judgments about their own minds.

Building Ethical Wearables: What Actually Helps

So what does ethical mental health wearable design look like in practice? Based on my research and the broader literature, here are the non-negotiables:

User control over data. Period. Safeguards should clarify data ownership, establish clear conditions for any external reporting, and promote individual control over personal information (Martinez-Martin & Kreitmair, 2018).

Transparent algorithms. Users deserve to know how their device reaches conclusions about their mental state. No black boxes.

Meaningful consent. Not just a checkbox. Actual understanding of what you are agreeing to, presented in plain language.

Purpose limitation. Data collected for health support should not be repurposed for advertising, employment screening, or other uses without explicit additional consent.

Special protections for vulnerable groups. Including autistic adults, people with intellectual disabilities, and anyone else who may face barriers to fully informed decision-making.

The Line We Should Not Cross

The line is actually pretty clear when you think about it. Mental health wearables should support autonomy, not undermine it. They should empower users to understand and manage their own wellbeing, not turn them into data sources for third parties.

My patent work on multi-sensory assistive wearable technology is built around this principle (Ruttenberg, 2025a). The point is not to monitor people. The point is to give people tools that help them navigate a world that was not designed for their neurology.

That is a fundamentally different project than building surveillance tools disguised as wellness devices.

What You Can Do

If you are using or considering a mental health wearable, ask yourself a few questions:

Do I understand what data this device collects?

Do I know who has access to that data?

Can I control when and how my data gets shared?

Does this device fit my lifestyle and comfort level?

Consumers should understand whether mental health wearables align with their values and whether they are comfortable with health decisions being influenced by external devices rather than solely their own judgment and healthcare provider input (Martinez-Martin & Kreitmair, 2018).

The technology is not going away. But we get to decide what kind of technology we build and what kind we accept. Let us choose wisely.

Dr David Ruttenberg PhD, FRSA, FIoHE, AFHEA, HSRF is a neuroscientist, autism advocate, Fulbright Specialist Awardee, and Senior Research Fellow dedicated to advancing ethical artificial intelligence, neurodiversity accommodation, and transparent science communication. With a background spanning music production to cutting-edge wearable technology, Dr Ruttenberg combines science and compassion to empower individuals and communities to thrive. Inspired daily by their brilliant autistic daughter and family, Dr Ruttenberg strives to break barriers and foster a more inclusive, understanding world.

References

Burr, C., & Cristianini, N. (2019). Can machines read our minds? Minds and Machines, 29(3), 461-494.

Huckvale, K., Torous, J., & Larsen, M. E. (2019). Assessment of the data sharing and privacy practices of smartphone apps for depression and smoking cessation. JAMA Network Open, 2(4), e192542.

Martinez-Martin, N., & Kreitmair, K. (2018). Ethical issues for direct-to-consumer digital psychotherapy apps: Addressing accountability, data protection, and consent. JMIR Mental Health, 5(2), e32.

Ruttenberg, D. (2020, May 3). PPI Questionnaire on Adaptive Wearable Appropriateness as an Autistic Intervention. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/a3jbz

Ruttenberg, D. (2023, April 9). Safeguarding Autistic Adults Who Use Technology. https://www.local.gov.uk/. https://doi.org./10.17605/OSF.IO/5PJRV

Ruttenberg, D. (2025a). Multi-sensory, assistive wearable technology, and method of providing sensory relief using same. U.S. Patent US-12,208,213 B2 issued 28 January 2025.

Ruttenberg, D. (2025b). Towards technologically enhanced mitigation of autistic adults' sensory sensitivity experiences and attentional, and mental wellbeing disturbances. [Doctoral dissertation, University College London]. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.16142.27201

Comments