Fighting the Distraction Engine: How Neuroscience Can Improve AI Focus

- David Ruttenberg

- 4 days ago

- 5 min read

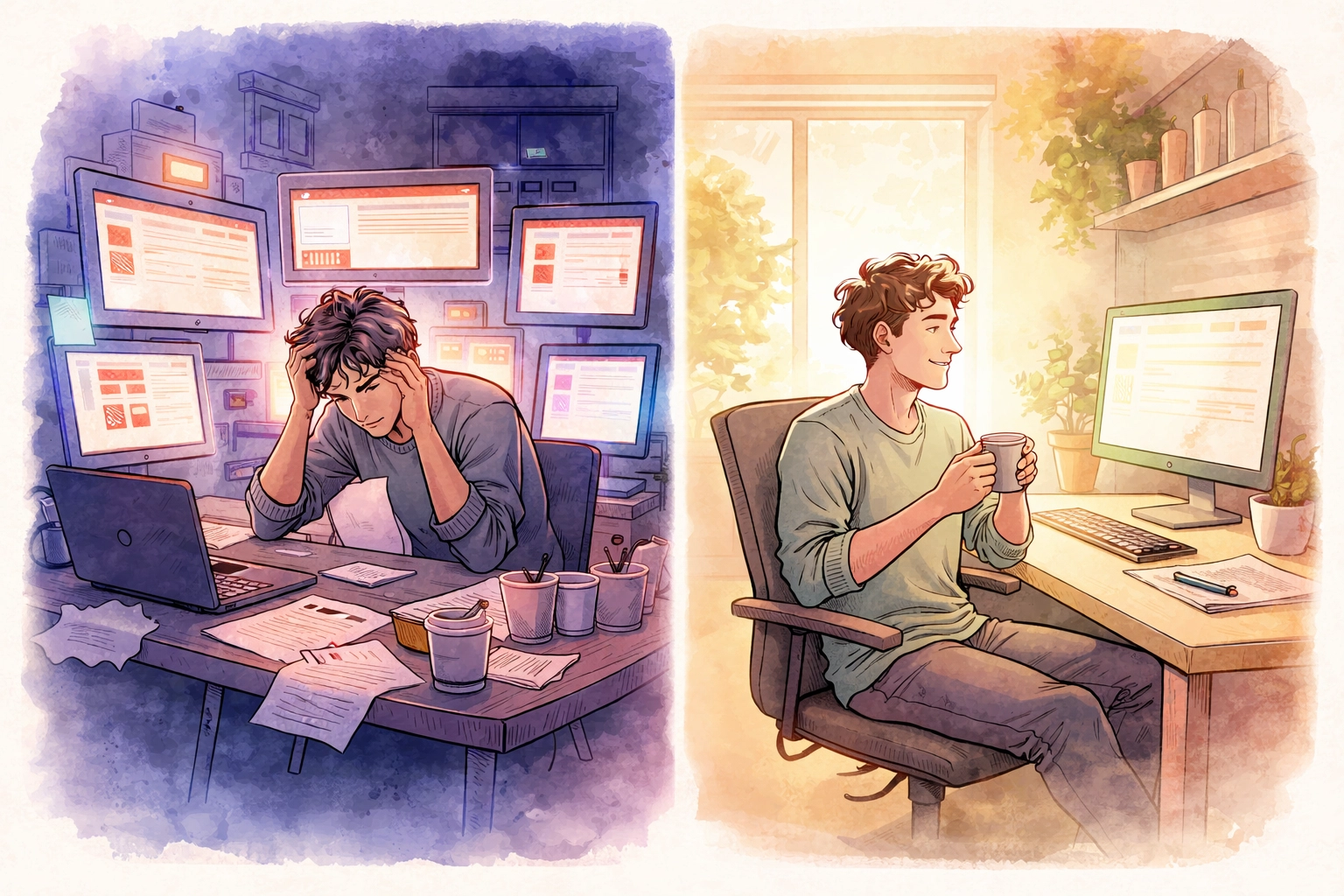

Let's be honest: most of the technology we use every day wasn't designed to help us focus. It was designed to capture our attention and keep it hostage.

From infinite scroll feeds to notification bombardment, modern AI systems have become remarkably good at one thing: distraction. And for neurodivergent individuals who already navigate complex attentional landscapes, this "distraction engine" can be genuinely harmful.

But here's the good news: the same neuroscience that explains why these systems hijack our attention can also show us how to build better ones.

The Attention Economy's Hidden Cost

We live in what economists call the "attention economy." Your focus is the product, and AI algorithms are optimized to extract as much of it as possible. Every ping, every autoplay video, every "you might also like" recommendation is engineered to keep you scrolling.

For neurotypical users, this is annoying. For neurodivergent individuals: particularly those with ADHD, autism, or sensory processing differences: it can be genuinely disabling.

Research has consistently shown that environmental factors significantly impact cognitive performance, especially for those with sensory sensitivities. My own research at University College London demonstrated that sound impairment and environmental disruptions directly affect cognitive skill performance, with neurodivergent individuals showing heightened vulnerability to these disruptions (Ruttenberg et al., 2020).

When we layer AI-driven distractions on top of already challenging sensory environments, we create a perfect storm for attentional collapse.

What Neuroscience Tells Us About Focus

Here's what's fascinating: attention isn't a single thing. Neuroscientists break it down into multiple systems: selective attention (filtering what matters), sustained attention (staying focused over time), and divided attention (managing multiple streams of information).

For many neurodivergent individuals, these systems work differently. Not worse: differently. Someone with autism might have extraordinary selective attention for topics of interest while struggling with attention switching. Someone with ADHD might excel at divided attention in stimulating environments but struggle with sustained attention during monotonous tasks.

The problem? Most AI systems are designed with a one-size-fits-all model of human attention that doesn't account for this diversity.

My PhD research examined how technological interventions could be designed to work with neurodivergent attention patterns rather than against them (Ruttenberg, 2025). The findings were clear: when technology respects individual attentional differences, outcomes improve dramatically.

The Safeguarding Gap

There's another dimension to this problem that doesn't get enough attention: safety.

Distraction-optimized AI doesn't just waste time: it can put vulnerable individuals at risk. When someone with autism is overwhelmed by sensory input from multiple AI-driven notifications while trying to navigate a complex situation, the consequences can be serious.

In my work with the Local Government Association, I highlighted how technology design often fails to consider the safeguarding needs of autistic adults (Ruttenberg, 2023). Systems that constantly compete for attention create cognitive overload, reducing the capacity for decision-making and increasing vulnerability to manipulation or harm.

This isn't just a usability issue: it's an ethical one.

Designing for Focus, Not Distraction

So what does neuroscience-informed AI look like? Here are the core principles:

1. Respect Attentional Capacity

Instead of maximizing engagement, design for optimal attention allocation. This means understanding that attention is a limited resource and that exceeding someone's attentional bandwidth doesn't create value: it destroys it.

2. Personalize for Neurodiversity

Neural-inspired AI models can enable greater adaptability by mimicking the brain's hierarchical organization and modular processing. This approach allows systems to learn and respond to individual attentional patterns rather than forcing users into neurotypical templates.

3. Reduce Sensory Competition

The UK Parliament's POSTnote on invisible disabilities emphasized that workplace and educational environments often fail to accommodate sensory processing differences (Ruttenberg et al., 2023). The same is true for digital environments. AI systems should minimize competing sensory demands, not amplify them.

4. Support Attention Switching

Rather than fighting for attention through interruption, well-designed AI should support natural attention transitions. This means providing clear signals, respecting task completion, and allowing users to control when they shift focus.

5. Build in Recovery Time

Sustained attention depletes cognitive resources. Neuroscience-informed AI should recognize attentional fatigue and build in natural recovery periods rather than pushing users toward burnout.

From Theory to Practice

These principles aren't just theoretical. They're already being applied in assistive technology design.

My research on multi-sensory assistive wearables specifically addressed how technology can mitigate sensory sensitivity experiences and attentional disturbances in autistic adults (Ruttenberg, 2025). The approach centers on working with the brain's natural processes rather than against them.

The emerging field of neuromorphic computing: AI systems that more closely mirror biological neural processes: offers promising pathways for creating technology that supports rather than hijacks human attention. When we design AI that aligns with how the brain actually works, we create tools that enhance human capability instead of exploiting human vulnerability.

The Business Case for Better Design

Here's something that might surprise the tech industry: designing for focus is actually good business.

Users who feel respected and supported by technology become loyal advocates. Products that help people accomplish their goals: rather than trapping them in engagement loops: build genuine value. And as awareness of neurodiversity grows, companies that design inclusively will have significant competitive advantages.

The distraction engine might maximize short-term engagement metrics, but it's burning through user trust at an unsustainable rate.

What You Can Do

If you're a technology designer, start by questioning engagement-maximizing defaults. Ask whether your AI systems are serving users or exploiting them.

If you're a policymaker, consider how regulation can incentivize attention-respecting design, particularly for vulnerable populations.

If you're a neurodivergent individual navigating these systems, know that the problem isn't you. The technology wasn't designed with your brain in mind: but it should be.

The fight against the distraction engine isn't just about productivity. It's about building technology that respects human cognitive diversity and supports human flourishing.

That's a fight worth having.

Dr David Ruttenberg PhD, FRSA, FIoHE, AFHEA, HSRF is a neuroscientist, autism advocate, Fulbright Specialist Awardee, and Senior Research Fellow dedicated to advancing ethical artificial intelligence, neurodiversity accommodation, and transparent science communication. With a background spanning music production to cutting-edge wearable technology, Dr Ruttenberg combines science and compassion to empower individuals and communities to thrive. Inspired daily by their brilliant autistic daughter and family, Dr Ruttenberg strives to break barriers and foster a more inclusive, understanding world.

References

Ruttenberg, D. (2025). Towards technologically enhanced mitigation of autistic adults' sensory sensitivity experiences and attentional, and mental wellbeing disturbances [Doctoral dissertation, University College London]. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.16142.27201

Ruttenberg, D. (2023, April 9). Safeguarding autistic adults who use technology. Local Government Association. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5PJRV

Ruttenberg, D., Porayska-Pomsta, K., White, S., & Holmes, J. (2020, May 3). Sound impairment effect on cognitive skill performance. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/fng7d

Ruttenberg, D., Rivas, C., Kuha, A., Moore, A., & Sotire, T. (2023, January 12). Invisible disabilities in education and employment. United Kingdom Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology POSTnote, (689), 1-23.

Comments